Capitalization-Weighted Indexes, RAFI, “Smart Beta,” and Factors (JPM Series)

Capitalization-weighted indexes and portfolios are popularity-weighted and tilted toward growth and momentum. This means, they overweight and underweight stocks that subsequently lag and outperform the market, respectively.

As a term, smart beta has been so misapplied that it has outlived its usefulness and ought to be retired.

Like other value-based strategies, RAFI sells at a discount compared to the cap-weighted markets and its performance runs in parallel with the value cycle.

Cap-weighted strategies are making speculative predictions about the size and shape of the future economy. Fundamental strategies like RAFI are weighting companies based on their current footprint in the publicly traded macroeconomy.

This is part of a series of articles adapted from my contribution to the 50th Anniversary Special Edition of The Journal of Portfolio Management.

Introduction

Index funds emerged in the early 1970s and were designed to match rather than beat the market. For decades, they were associated with the capitalization-weighted (CW) market indexes that defined their investment approach. Index funds are widely described as “passive” investments because they trade very little. But at the bottom of the list, where stocks are added and dropped, index funds are very active, trading as much as 25% of a company’s total market value in a single day, much of that in a single market-on-close block trade.

Create your free account or log in to keep reading.

By design, a stock’s overall weight in a CW index fund increases as its stock price increases relative to others. The result is a portfolio that systematically overweights the companies that are destined to underperform the market and underweights those that are destined to outperform, relative to the unknowable ‘fair value’ weighting. Index providers and index fund managers have always readily acknowledged this simple truth. They suggest this observation is useless unless we can identify which companies are overvalued and which companies are undervalued. In an efficient market, the future business prospects of a company are fully reflected in the share price, so the future risk-adjusted returns will be uncorrelated to the starting relative valuation.

As there are enough nuances in capitalization-weighted indexing to fill many thousands of pages, I will explore capitalization-weighted indexes in the narrower context of fundamental indexes and smart beta. Do CW indexes undermine price discovery? Do they increase or decrease market efficiency? Is there any reason to think that their stupendous growth in recent decades will ever reverse? These are worthy topics that we sadly cannot address here.

By design, a stock’s overall weight in a CW index fund increases as its stock price increases relative to others. The result is a portfolio that systematically overweights the companies that are destined to underperform the market and underweights those that are destined to outperform, relative to the unknowable ‘fair value’ weighting.

”In 2005, we introduced the Fundamental Index (RAFI), challenging the idea that passive investing must be capitalization-weighted. In fact, alternative investment strategies could be offered as rules-based, transparent, low-turnover index constructs. RAFI inspired Towers Watson to coin the expression “smart beta,” in 2007. Initially, smart beta referred to index strategies that did not weight stocks in proportion to share price, market capitalization, or relative valuation multiple and, therefore, could capture a rebalancing alpha whenever the market overreacted to news. Because “smart beta” sounds smart, many organizations began attaching the term to a vast array of ideas and strategies, including many that were not at all smart. As various smart beta and factor investing strategies and products proved disappointing, they (and the term smart beta) fell out of favor.

Consider the “noise in price” model, where the share price for a company equals its unknowable fair value, that follows a random walk, plus or minus a mean-reverting error term. In a world of mean reversion, even for pricing error, we are rewarded for breaking the link between price and index weight.1 Whether we construct the portfolio using equal-weighting, fundamental-weighting (an optimization that doesn’t anchor on cap-weighting), or even darts, we turn the mean-reverting error term into an alpha.2 In 2005, Jack Treynor showed that this alpha would be a function of the variance of that mean-reverting error term and the speed of that mean reversion.

Have smart beta and factor investing strategies become myths that have rightly fallen out of favor? Smart beta became such a broad catchall category, spanning strategies that are both good and bad, that the term lost all meaning. Sadly, the term now belongs in the dustbin of history.

For factor investing, there are three caveats. First, a company is not an assortment of factor exposures. It consists of people, products, strategies, and guiding principles. Second, multifactor backtests are not reliable because too many backtests are heavily data-mined. Third, factor investing was oversold as a panacea that could not fail the patient investor. That said, some superb work is done in the factor arena, and well-crafted multifactor strategies that are not the result of heavy data mining have merit. Again, a thorough exploration of Factorland could fill volumes. In the interest of brevity, I will leave that exploration for another day.

Smart beta became such a broad catchall category, spanning strategies that are both good and bad, that the term lost all meaning. Sadly, the term now belongs in the dustbin of history.

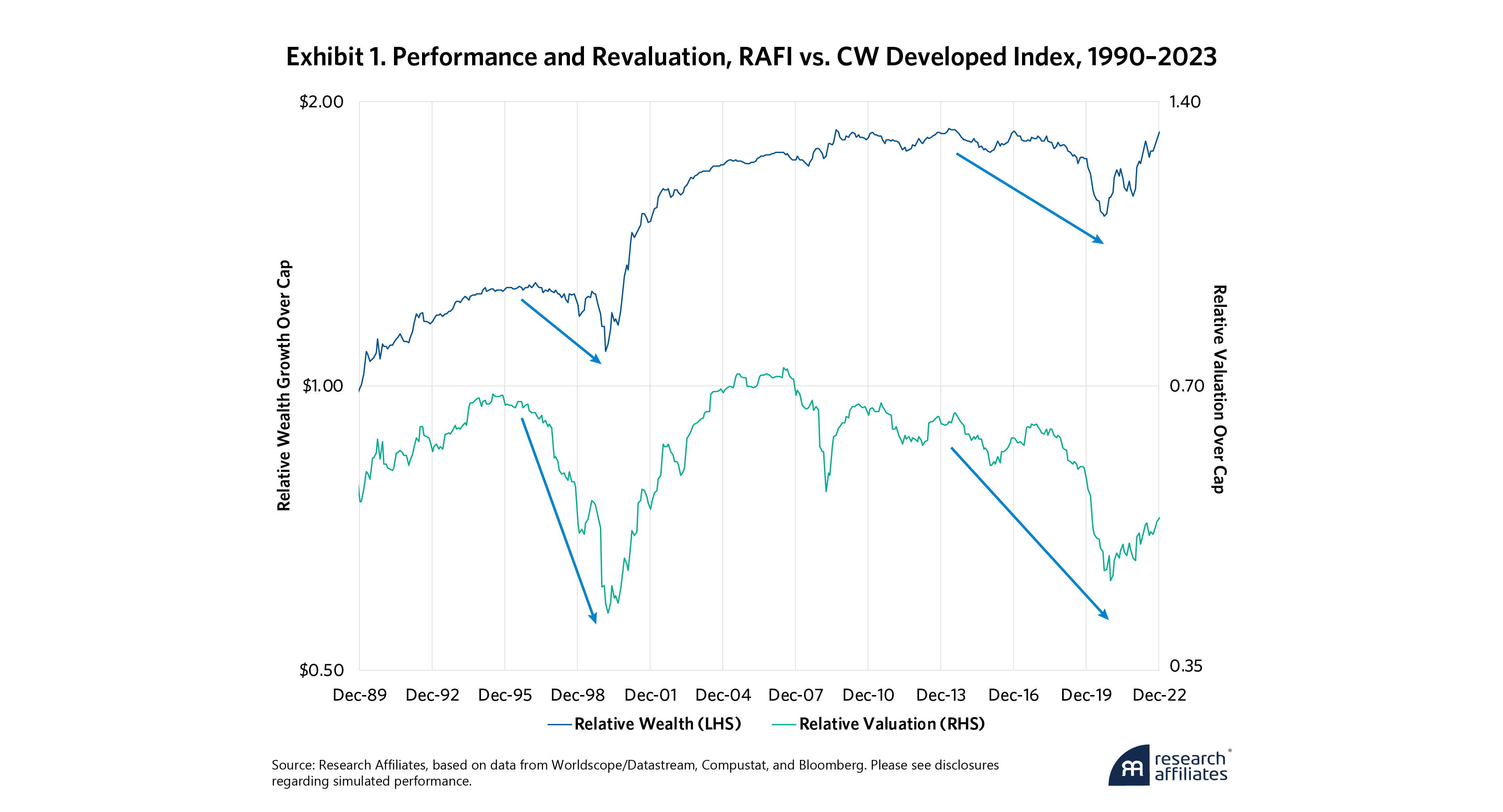

”RAFI is perhaps my most controversial contribution to our industry over the past half-century.3 Like the value factor and conventional value indexes, RAFI trades at a substantial discount to the broad CW markets, so its performance rises and falls in parallel with the value cycle. The blue arrows in Exhibit 1 show that, between March 1997 and February 2000, and again from year-end 2016 through August 2020, the RAFI Developed Index lagged the CW Developed World Index by a wide margin. During the dot-com bubble, the relative wealth of the RAFI investor fell from 1.30 to 1.11, underperforming the passive investor in the CW market by 15%. During the more recent value crash, the relative wealth of the RAFI investor fell from 1.93 to 1.57, thereby lagging the CW market investor by 19%. In the intervening span from 2000 through 2016, RAFI Developed achieved multiple performance peaks relative to the CW Developed, in marked contrast with conventional value investing.

The relative valuation of the RAFI Developed World Index trades at a discount, by construction. Growth stocks are reweighted down to match the macroeconomic footprint of the underlying business, based on a blend of measures like sales, cash flow, book value plus intangibles, and dividends plus buybacks. Stocks trading at premium valuation multiples are reweighted down, proportional to their relative valuation premiums. Value stocks are reweighted up, proportional to their relative valuation discounts, to match their macroeconomic footprint.

But the discount for a RAFI portfolio is not static. In the dot-com bubble, the relative valuation of RAFI Developed fell from 0.75 to 0.48, becoming cheaper relative to CW Developed by 34%, which dwarfs the 15% underperformance. RAFI’s underperformance was a consequence of the valuation multiples tumbling; the underlying businesses were doing just fine! In the more recent span of disappointment from year-end 2016 until the summer of 2020, RAFI Developed grew cheaper relative to MSCI World by 28% (a drop from 0.71 to 0.51), which again dwarfs RAFI’s 19% underperformance. As with conventional value investing, the RAFI portfolio of companies fared very well, even as the stocks were lagging the CW market. In aggregate, the cash flow, sales, dividends and book value of the companies in the RAFI portfolio fared better than the broad market, even as their stocks were falling out of favor.

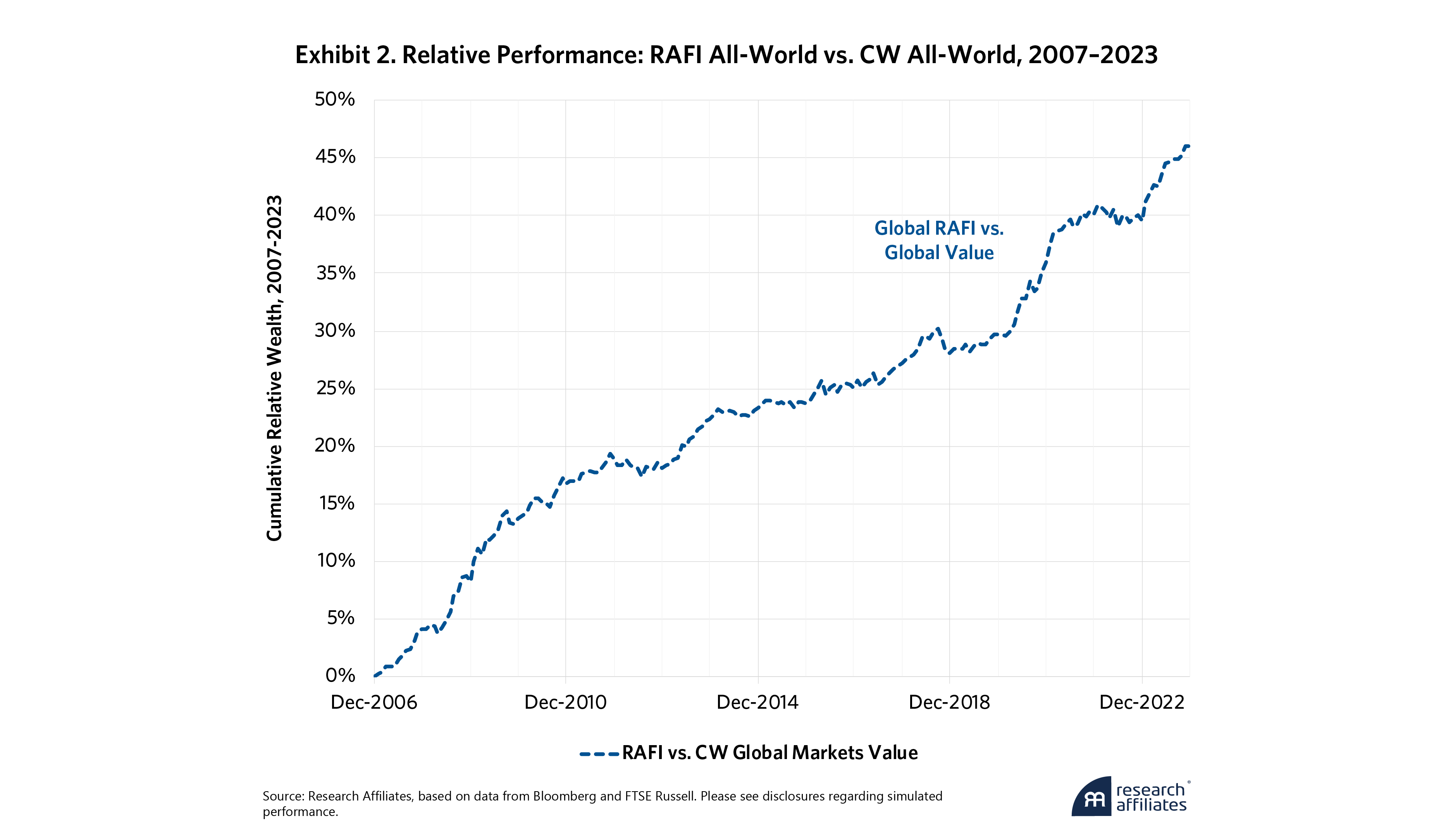

To be sure, RAFI did not exist in 1990. RAFI indexes for U.S. large, U.S. small, International, and Emerging Markets were all launched between year-end 2004 and mid-2006. Accordingly, our evaluation of RAFI’s out-of-sample performance relative to value begins in 2007 (or a bit earlier, depending on the specific application). Exhibit 2 shows the relative performance of RAFI All-World against a CW All-World value benchmark from 2007 through 2023.

This relative performance averages 2.4% per annum, with 2.1% tracking error (falling to 1.4% when quarterly rebalancing was introduced in 2010). The deepest drawdown is 2.6%. The longest drawdown is just eight months, peak to trough. And the t-statistic is 4.6 (rising to 6.2 once quarterly rebalancing was introduced in 2010). These are live index results.4 A backtest with a t-statistic of 3 is uncommon. Critics have some explaining to do, in dismissing a strategy with a live t-statistic that ranges as high as 6.

Binocular Vision: Do We Forget That Stocks Are Companies?

Business schools and finance literature teach a cap-weight-centric worldview. Companies have attributes that we can quantify as factors: size, profit margins, volatility, valuation multiples, tangible and intangible assets, growth rates, and so forth. The squishy intangibles are largely left to the domain of behavioral finance. With binocular vision, we can also look at the world through an economy-centric lens and gain a richer perspective. This has relevance to the realm of indexing. Capitalization-weighted indexes mirror the look and composition of the stock market. RAFI mirrors the look and composition of the publicly traded macroeconomy. Both perspectives have merit.

A cap-weight-centric perspective limits us to thinking of the market as neutral. From a cap-weight-centric vantage point, the future will be dominated by companies with the vision to shape that future. In my view, these companies deserve most of our investment capital. They will grow to become world-straddling colossi. Today’s “Magnificent Seven” are an illustrative example. We need to recognize that the market is making large active bets relative to the economy, deciding which companies and sectors will dominate our future. The market will get some things right and some things wrong.

We need to recognize that the market is making large active bets relative to the economy, deciding which companies and sectors will dominate our future.

”From a cap-weight-centric perspective, RAFI looks like a clever repackaging of value investing, with fundamental weights that equal the cap-weight divided by a blend of relative price-to-fundamentals ratio. Reciprocally, from an economy-centric worldview, the CW market is pre-paying for a future that we cannot accurately know. From this economy-centric perspective, the cap-weighted market portfolio is a growth-tilted, momentum-chasing, popularity-weighted index. RAFI’s bets relative to the cap-weighted market portfolio are a near-exact mirror image of the cap-weighted market’s willingness to pay up for growth that has not yet happened.

Please read our disclosures concurrent with this publication: https://www.researchaffiliates.com/legal/disclosures#investment-adviser-disclosure-and-disclaimers.

End Notes

1. If the error in price at time t+1 equals some fraction (less than 1) of the error in price at time t, plus a new random shock in either direction, we have a mean-reverting error term.

2. See Arnott, et al. (2013), “The Surprising Alpha from Malkiel’s Monkey and Upside-Down Strategies,” for an exploration of this idea.

3. See Arnott, Hsu, and Moore (2005). Fundamental Indexation. The Fundamental Index (RAFI) is constructed by examining the fundamental scale of the business of publicly traded companies. RAFI uses fundamental measures of company size—for example, sales, profits, net worth, and dividends—to select and weight companies in the index in rough proportion to the macroeconomic footprint of the business, irrespective of current share price. As company fundamentals typically move slower than price, this also introduces a rebalancing discipline, contratrading against the market’s constantly shifting expectations, whenever share price movements are not confirmed by like movements in the underlying fundamentals of a business. Because RAFI down-weights growth stocks and up-weights value stocks to match their economic footprint, it will always have a stark value tilt relative to the capitalization-weighted stock market.

4. To avoid cherry-picking, we use an equal-weighted average of the FTSE RAFI, Russell RAFI, and RA RAFI indices, from their respective start dates; then we compare the results with the equal-weighted average of MSCI ACWI and FTSE All World index returns. Again, to avoid cherry-picking, we also use the all-world rather than focusing just on U.S. large or small, international or emerging markets.

References

Arnott, Robert D., Jason C. Hsu. and Philip Moore. 2005. “Fundamental Indexation.” Financial Analysts Journal 61 (2): 83–99.

Arnott, Robert D., Jason C. Hsu, Vitali Kalesnik, and Phil Tindall. 2013. “The Surprising Alpha from Malkiel’s Monkey and Upside-Down Strategies.” The Journal of Portfolio Management 39 (4): 91–105.

Treynor, Jack L. 2005 “Why Market-Valuation-Indifferent Indexing Works.” Financial Analysts Journal, 61 (5): 65–69.